Original: https://www.opendemocracy.net/transformation/alex-khasnabish-max-haiven/why-social-movements-need-radical-imagination

This is an edited excerpt from The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity, published by Zed Books June 2014. In this book, we try to better understand the way that the imagination animates movements for social change today. Based on that understanding, we want to reframe the purpose of social movement research.

At its most superficial, the radical imagination is the ability to imagine the world, life, and social institutions not as they are but as they might otherwise be. It is the courage and the intelligence to recognize that the world can and should be changed. The radical imagination is not just about dreaming of different futures. It’s about bringing those possibilities back from the future to work on the present, to inspire action and new forms of solidarity today.

Likewise, the radical imagination is about drawing on the past, telling different stories about how the world came to be the way it is, remembering the power and importance of yesterday’s struggles, and honouring the way they live on in the present.

The radical imagination also represents our capacity to imagine and make common cause with the experiences of other people. It undergirds our ability to build solidarity across boundaries and borders, real or imagined. In this sense, it is the basis of solidarity and the struggle against oppression, which are key to building of robust, resilient, and powerful movements. Without the radical imagination, we are left only with the residual dreams of the powerful and, for the vast majority, they are experienced not as dreams but as nightmares of insecurity, precarity, violence, and hopelessness. Without the radical imagination, we are lost.

We approach the radical imagination not as a thing that individuals possess in greater or lesser quantities but as a collective process, something that groupsdo and do together through shared experiences, languages, stories, ideas, art, and theory. Collaborating with those around us, we create multiple, overlapping, contradictory, and coexistent imaginary landscapes, horizons of common possibility and shared understanding. These shared landscapes are shaped by and also shape the imaginations and the actions of those individuals who participate in them.

The concept of the “radical” inherits its most powerful meaning from the Latin word for “rooted,” in the sense that radical ideas, ideologies, or perspectives are informed by the understanding that social, political, economic, and cultural problems are outcomes of deeply rooted and systemic antagonisms, contradictions, power imbalances, and forms of oppression and exploitation.

As a result, radicalism does not so much describe a certain set of tactics, strategies, or beliefs. Rather, it speaks to a general understanding that, even if the system as a whole can be changed through gradual institutional reforms, those reforms must be based on and aimed at a transformation of the fundamental qualities and tenets of the system itself. The idea of radicalism cannot be monopolized by any one point on the political spectrum: fundamentalists, far-right militias, neoconservative pundits, and others also display elements of radicalism as much as (sometimes more than) the anarchist organizers, anti-racist activists, feminist campaigners, or independent journalists, academics, and writers who make up the cast of characters in this book.

Based on this approach, we understand social movements are convocations of the radical imagination: they are convened (collectively called into being) by individuals who share some understanding and imagination of the world in a radical sense. That is, they see the problems confronting us as deeply rooted in social institutions and systems of power and, importantly, they believe these institutions and systems can and should be changed. While social movements may be many things and take many forms, we suggest that at least one dimension that binds them together is the (sometimes intentional, sometimes incidental) cultivation of common imaginary landscapes, something which is an active process, not a steady state.

So we can say that social movements are animated by the radical imagination. This is not to say that all members share identical imaginary landscapes; the driving dynamic of social movements are the tensions and conflicts and dialogues between imaginative actors. The radical imagination is no static thing to be studied under the microscope or measured through quantitative analysis. It must be observed as it “sparks” from the friction between individuals, groups, ideas, strategies, and tactics. Indeed, the radical imagination emerges from the conflicts and tensions germane to the experience of a highly unequal world. And for that reason, the radical imagination often emerges most brilliantly from those who encounter the greatest or most acute oppression and exploitation, and is often stunted and diluted in those who enjoy the greatest privileges.

A double crisis of social movements

We understand that social movements and the radical imagination today are caught in a contradiction, one we identify as a “double crisis” of social reproduction. Social reproduction here refers to the dense network of relationships and forms of labour that reproduce social life, and conversely the assemblage of forces necessary to reproduce those relationships and forms of labour. Capitalism, neo-colonialism, patriarchy and white-supremacy are all systems of power that are reproduced by the actions of and relationships between people, but also reproduce people and relationships. We, as individuals, reproduce ourselves within our communities, and we also reproduce our communities, warts and all.

On the one hand, social movements inherently envision and seek to bring about a radical change in the way society is reproduced. Whether they seek to alter government policy, institutional and organizational systems or cultural norms, movements do not want society to be reproduced in its current form. This is especially, but not exclusively, the case for radical social movements that see the problems they face as deeply rooted in the social order, and recognize that a radical change to that order at its very roots is necessary if these problems are to be solved.

On the other hand, whether intentionally or not, social movements also become spheres of alternative social reproduction for their participants: spaces of identity formation, friendship, meaning, care, and possibility, though, as we shall see, they are never unproblematic utopias (far from it). They often seek to create, within their organizational forms or norms, a paradigmatic alternative to the society they seek to change, a tendency that has become much more conscious and common since the 1960s with the rise of “new social movements” and especially since the “anarchist turn” in the 1990s.

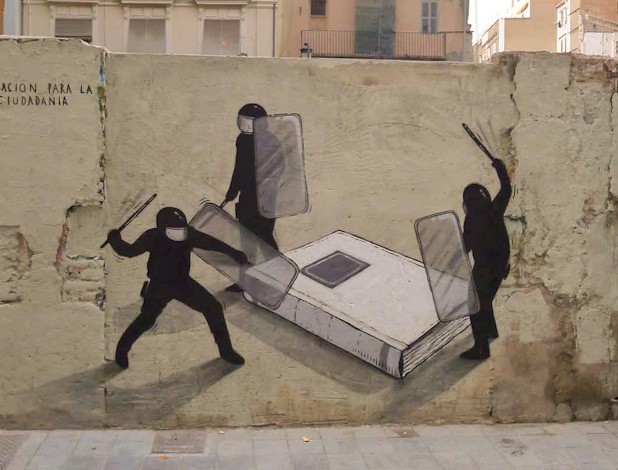

We pay attention to this tension because, to a very real extent, the crisis of social reproduction in global capitalist society is intensifying on at least three fronts. First, the ramping-up of neoliberalism in the form of an unapologetic and vicious austerity regime has seen the further subjugation of governments to the will of capital and the evisceration of what remained of the welfare state. Second, the “War on Terror” continues to justify the amplification of repression, surveillance, war, and policing around the world, as well as fortifying a culture of fear backed by racist fantasies and neocolonial ambitions. Third, the deepening ecological crisis, notably the increasing toxicity of the environment and the climate chaos unleashed by global warming, threatens to set loose yet unimagined terrors on the world’s populations, terrors that will likely be suffered and endured alone as governments and communities continue to be dismantled and capitalist impunity is enshrined.

The sum of these factors is a wholesale global crisis of social reproduction, where social life itself is made to pay the cost of the reproduction of a renegade, cancerous capitalist system. This crisis manifests as the intensification of fundamentalisms, prejudices, and hatreds, as well as a retreat further into competitive individualism and consumerism.

In these times, when the majority of us live increasingly isolated lives, social movements are not merely important as vehicles for patently necessary social change. They become islands of refuge in an uncaring world. On the one hand, in their organizational forms and group norms, they often strive to “prefigure” the world we might like to see, one that values individuality and communality, radical democracy and solidarity, equality and acceptance, passion and reason, hope and love. They often serve as spaces of friendship, community, romance, and empowerment. This is true even of those more severe and formal organizations and groups that intentionally disavow their social dimensions.

Yet at the same time, we and others have observed that movements and activists all too often fall prey to the crises of reproduction within their own organizations and movements. Sometimes this manifests as open conflicts over strategy and tactics. Other times (indeed, we’d suggest, usually) it manifests – at least on the surface – as personality conflicts or social tensions. Frequently, both of these are the result of the way the movement or group in question continues to reproduce the oppressive behaviours or patterns it has inherited from the society of which it is a part, notably tensions regarding masculinist behaviour, sexual politics and the continued devaluation of people of colour and other marginalized peoples.

In this book, we wanted to imagine and experiment with what “prefigurative” research might look like, a form of research borrowed from a post-revolutionary future of which we can only catch glimpses. We wanted to imagine a form of common research, beyond enclosure. In this, we hoped to do justice to the radical imagination by helping create the conditions of its emergence and flourishing.